The FracTracker Alliance (www.www.fractracker.org) recently produced a set of maps showing the population density along the route of the Dragonpipe (Mariner East 2 pipeline), and what they show is a route that runs through many centers of dense population while ignoring nearby areas where few people live. The maps are based on local population figures from the US Census. The lesson of these maps: Sunoco has put the Dragonpipe in a very bad location.

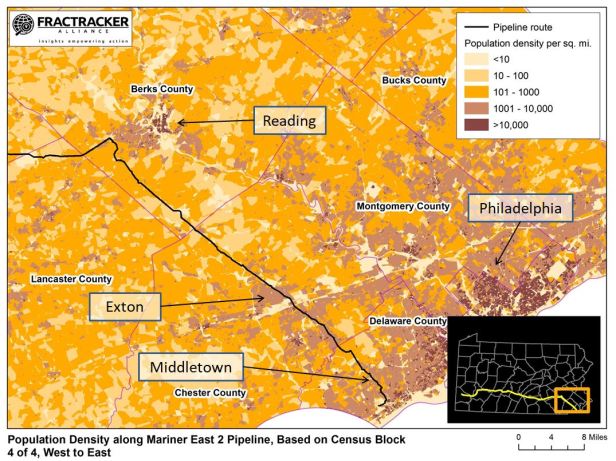

Here, for example, is a map of the route through Berks, Chester, and Delaware County.

The dark brown areas are the areas of dense population. The lighter the color, the lower the population density. The black line is the pipeline route.

In the upper left-hand part of the map, you can see that the route passes through the suburbs of Reading, in Berks County. In the lower part, it passes directly through population centers in Chester and Delaware County. We will take a closer look at those below.

Why this route? Sunoco’s convenience, that’s all. At a glance, you can see that the pipeline route is a very bad one. In many areas, it is actually the worst possible route that Sunoco could have chosen: it puts more people at risk than any other path they might have chosen with the same endpoints. Why in the world did they choose it?

The answer is: Sunoco’s corporate convenience. The Dragonpipe, for most of its length, runs side-by-side with Mariner East 1, an existing 80-year-old pipeline designed to carry gasoline and heating oil to customers in the central and western parts of the state. Of course the old pipeline had to go near areas of population: that’s where the customers for gasoline and heating oil were located back in the 1930s.

It was convenient for Sunoco to reverse the flow of the old pipe and to change its content to highly explosive “natural gas liquids” (NGLs). No public notification or review was required for those steps. It was also convenient to use the same right-of-way for its new Mariner East 2 and 2x pipelines.

But Sunoco’s convenience means unnecessary risks for tens of thousands of Pennsylvania residents.

Not only did the old pipeline connect the centers of population from the 1930s (which are much more populous now); in the southeastern part of Pennsylvania, the character of the area has changed dramatically. In the 1930s, when the original pipeline was built, the area it ran through in Delaware and Chester County was mostly farms. Now, that area is densely-settled suburbs, with homes, schools, businesses, hospitals, and shopping centers right next to the right-of-way.

The Exton area is a prime example of how these changes have led to a potentially disastrous pipeline route. Here is a more detailed map of the population density near Exton.

As you can see, the pipeline route sticks to high-density areas (brown) the entire way, even though low-density options (orange, yellow) exist nearby.

Sunoco (like any corporation) has a moral obligation to conduct its business in a safe manner, and that includes choosing a safe route for a pipeline it knows is dangerous. It did not do so. But more than that, it also had a legal obligation: in the settlement Sunoco reached last August with Clean Air Council, Delaware Riverkeeper Network, and Mountain Watershed Association, Sunoco agreed to consider alternative routing for the pipeline in this area. It simply ignored that part of the agreement. Instead, it dismissed the alternatives as “not practicable” because they did not involve the right-of-way it was already using for Mariner East 1.

Sunoco’s position seems to be: the only factor that matters in considering a pipeline route is whether Sunoco has an existing pipeline there. A better route would reduce by hundreds the number of people who could be killed if there were a leak and explosion, but that is not a factor that matters to Sunoco.

But pipelines do leak. Mariner East 1, in its short career as a pipeline carrying NGLs, has already leaked three times. It is just good luck that the leaks were stopped before the gas ignited. The Atex pipeline, a pipeline of similar size and content that runs down to the Gulf coast, ruptured and exploded near Follansbee, WV, in just its second year of operation. That’s what could happen with the Dragonpipe.

Sunoco has an obligation to do what it can to minimize the death and destruction caused by an event like the Follansbee one. That explosion was in a forested area. It took out several acres of trees but didn’t kill anyone. The result would have been far different if it had been in a densely populated area.

Just as the maps above show how the Philadelphia suburbs and those of Reading are threatened, other FracTracker Alliance maps will be available that show the threats to suburbs of Pittsburgh and Harrisburg.

Indeed, across the state, the Dragonpipe route seems to go out of its way to approach population centers. That may be convenient for Sunoco, but it is an unacceptable risk for Pennsylvania’s citizens to bear.

The route of Sunoco’s pipeline poses a tremendous threat to the population of south eastern Chester and Delaware counties.

LikeLike

There are a couple of prior incidents where large gas pipelines have ruptured in high-density residential neighborhoods.

The San Bruno, CA explosion of a Pacific Gas & Electric pipeline occurred at the dinner hour in the middle of an urban middle-class subdivision just south of San Francisco, destroying nearly 40 homes and damaging more than 100 others.

There is plenty of both ground-level and aerial video of the San Bruno gas pipeline explosion, which was initially-reported as an airliner crash, as the location is just a few miles from San Francisco Intl Airport.

No professional city planner would think that routing a major pipeline through a high-density population would be the safest place for it.

This day-after video of the San Bruno explosion is also quite good as a senior video reporter describes the inability of firefighters to do anything to fight the fire after the explosion ruptured local water mains.

This is a video of the San Bruno disaster produced by the NTSB.

The final death toll in San Bruno was 8 with several dozen injured.

Here is some video of an urban pipeline explosion in Taiwan in 2014:

This video is of the 36-inch gas pipeline explosion that burned a large Edison, NJ apartment complex to the ground in 1994. The Durham Woods apartment complex was a minimum of 900 feet from the fire. The video is pretty grainy, and was likely shot on low-grade video-recording equipment or even Super-8 movie film, but you get the idea nonetheless.

This is a New York Times piece on the explosion in Edison, NJ:

This is a good aerial video from a WTAE Pittsburgh news chopper of the aftermath of the Salem Twp, PA gas pipeline explosion in 2016 that shows well how far from such a pipeline is relatively safe in the event of such an explosion. That explosion was caused by the very early failure of a pipeline weld waterproofing tape product.

The home nearest the fire was 400 feet from the fire and was immediately-destroyed. Its owner suffered 2nd and 3rd-degree burns over 70% of his body but he lived because a passing motorist picked him up and rushed him to a hospital. The home further from the fire was 1800 feet away, and the heat of the fire melted the vinyl siding off the front of the house and off the side of their garage.

http://www.wtae.com/article/video-sky-4-surveys-incredible-damage-at-gas-pipeline-explosion-site/7198234

The fire shots in this video were taken a half-mile from the fire:

In the Salem Twp fire in a different longer video the local Fire Chief is quoted as saying that he drove his fire truck to a quarter mile from the fire and couldn’t even get out of his truck because the fire was so hot. He also said that the fire was far beyond his department’s capability to deal with.

This video was produced by the City of Bellingham, WA after their 1999 gasoline pipeline disaster. The Olympic gasoline pipeline ruptured at a stream crossing spilling a huge amount of gasoline into the stream, which flowed downhill through the city. Luckily there were only 3 fatalities, an 18 year old boy and two 10 year old boys, who were out in the large public park where the rupture occurred.

Now Bellingham, WA was a city of 70,000 people in 1999 with several suburbs. They had a large urban firefighting capability as well as central disaster management command, and they got lucky that the outcome wasn’t a whole lot worse too.

As a Master’s level urban & regional planner with many years of prior experience in the wholesale fresh food supply chain, warehousing, and distribution industry I know well that any modern society that runs heat, hot water, transportation, and numerous other industries off of fuel that we need some safe method of transporting fuel.

Given my experience and education I personally can’t rationalize the level of catastrophic risk in running a major gasoline or natural gas liquid pipeline through a heavily-populated urban area. The level of catastrophic risk is bad-enough running loads of gasoline to urban gas stations by heavy truck, and there have been numerous catastrophic incidents caused when gasoline tankers have gotten in accidents.

I have a crazy idea for routing this pipeline. Why not run it down a few miles off the east side of the Susquehanna River from below Harrisburg to North East River Bay, cross the bay, Elk Neck Park and Elk River, then run it through very low density farmland north of Middletown, DE, and then bring the pipeline up the Delaware River to Sunoco’s terminus at Marcus Hook? The pipeline could be also brought across under Back Creek which is low-density and would be several miles shorter than cutting-across open land north of Middletown.

After all there are two major underwater pipelines that cross Mackinac Strait under 4.5 miles of fresh water that 100 million plus Americans and Canadians depend-on for their water supply, the twin 20-inch Enbridge Line 5 pipelines, which were built in 1953, so the technology necessary to run fuel pipelines under major sensitive waterways has existed for 65 years at the minimum.

Sure it would cost Sunoco a lot more to run the pipeline underwater maybe 15 or 20 miles out of route but the level of catastrophic risk would diminish greatly. A plus would be that the route I have laid-out would pass several other refineries and this pipeline routing could haul their products too.

The most low-density spot I could find to enter North East River Bay is here about a half-mile south of Seneca Point, MD. The fact is that this routing could be built without coming within 1000 feet of anyone’s house except underwater coming across Back Creek.

https://www.google.com/maps/@39.5626159,-75.9961652,2239m/data=!3m1!1e3

LikeLike

Thanks for these examples, Mark. I would note that all of them (with the possible exception of the one in Taiwan) involve materials that are less explosive than the NGLs that Sunoco wants to put through the Dragonpipe. Your suggested alternative routes are a great improvement, but would still involve enormous risks to many people.

LikeLike

When a pipeline is run in a rural area like existed in Chester County back in 1930, the pipeline construction company needs to clear trees which forms a path that’s readily paved and developed into a main roadway. I think that’s what happened when Mariner East was installed some 80 years ago. Once there was a road, development sprang up along the route. The roads branched out over the decades until you have the population density you see now. To take a pipeline that carries a comparatively benign liquid like diesel fuel running through an area with this sort of population density and replace it with highly explosive [because of the high pressure] natural gas liquids – well there should be a law that prohibits this happening with a 60 day notice to a federal agency.

LikeLike